share

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with a pharma expert, for a deep dive into Long Range Planning (LRP) in the pharmaceutical industry. What unfolded was a masterclass in how leading pharma organizations plan not just for the next quarter, but for the next 3–10 years — across demand, supply, risk, and network complexity.

🚨 And it all starts at the molecule level — not just product families. Here’s a structured breakdown of the conversation, enriched with examples and insights you might find useful.

🧭 Where LRP Fits in the Supply Chain Planning Hierarchy

To set the context, pharma supply chain planning typically works across three key layers:

- SOE (Schedule of Execution): Near-term, 1-month out planning. Focuses on batch scheduling, resource allocation, and execution alignment.

- S&OP (Sales & Operations Planning): Rolling 2–4 months horizon. Aligns commercial forecasts with supply capability.

- LRP (Long Range Planning): Strategic, Year 1 through Year 3+ outlook. Anchors investment, capacity, and network strategy.

LRP is the strategic layer that influences the structure and agility of the entire supply chain.

🔍 Why Long-Range Planning Matters in Pharma?

Unlike annual planning or S&OP cycles, Long Range Planning is strategic and foundational. It touches every part of the value chain — from portfolio design and regulatory filings to supply chain architecture and capital investments.

The pharmaceutical industry, given its long development cycles, regulatory hurdles, and market volatility, demands molecule-specific strategic foresight.

1. Demand Planning: It Starts with the Right Questions

A strong long-range plan begins with a clear understanding of molecule-level demand trends.

🧪 Molecule-Level Segmentation:

You don't just plan for “oncology” or “diabetes” — you plan for specific APIs or drug candidates.

- Sprinters: Fast-growing molecules (e.g., Semaglutide in the GLP-1 class)

- Steady Horses: Predictable demand (e.g., Atorvastatin, Metformin)

- Laggards: Declining due to resistance or competition (e.g., some cephalosporins)

- Orphan/Niche: High-margin, low-volume (e.g., Nusinersen)

Example: With obesity on the rise, Semaglutide sees a 5-year demand surge — this drives specific capacity and sourcing plans.

🌍 Market Expansion at Molecule Level:

When entering new markets, planning must focus on:

- Regulatory filings per molecule (e.g., US ANDA for a generic, EMA for a biosimilar).

- Country-specific therapeutic preferences (e.g., metformin vs. newer diabetes drugs in emerging vs. developed markets).

📈 Pipeline and Generics:

- Patent cliffs are identified at the molecule level.

- Planning for biosimilar opportunities is molecule-dependent (e.g., Adalimumab biosimilars).

- Molecule lifecycle management: Is the API going off-patent? Are new indications being explored?

Example: The team may plan a generic version of Revlimid (Lenalidomide) based on patent expiry in 2026, targeting 3 regions with staggered filings

2. Supply Planning: From Molecule to Manufacturing Line

🏣 Line Loading by Molecule:

Each line must be mapped to specific molecules or dosage forms (e.g., oral solids vs. injectables).

- What are the annual volumes per molecule?

- Are there cross-contamination risks (e.g., penicillin APIs)?

- Are lines dedicated or flexible for molecule families?

💸 CapEx vs. OpEx at Molecule Level:

- Add new lines for key growth molecules (e.g., high-potency oncology APIs).

- Outsource niche or low-volume molecules to CMOs.

- Consider insourcing high-margin molecules where long-term ROI justifies CapEx.

Example: A plant might invest in contained suites to produce high-potency APIs like Abiraterone Acetate.

API Sourcing Strategy:

Secure long-term contracts for strategic molecules. Consider dual sourcing for critical APIs to reduce dependency on one geography.

3. Risk Planning: Molecule-Level Scenario Thinking

Risk scenarios must also be molecule-specific:

-

- Will regulatory approvals for a molecule be delayed?

- Are raw material precursors for a molecule sourced from high-risk regions?

- Will demand forecasts for that molecule shift due to therapy alternatives?

Example: A company producing Hydroxychloroquine faced a demand shock during COVID-19 and had to reallocate production capacity at short notice.

🧹 Network Design: Molecule-Centric Supply Chains

Your entire network design should reflect molecule flows — not just volumes.

- Map each molecule from source (API) to formulation site to finished goods warehouse.

- Evaluate costs, tariffs, service levels, and regulatory risks at each step.

- Include molecule-specific constraints like cold chain or hazardous handling.

Example: An API for a temperature-sensitive biologic may require a dedicated lane with GDP-compliant warehouses in 3 countries.

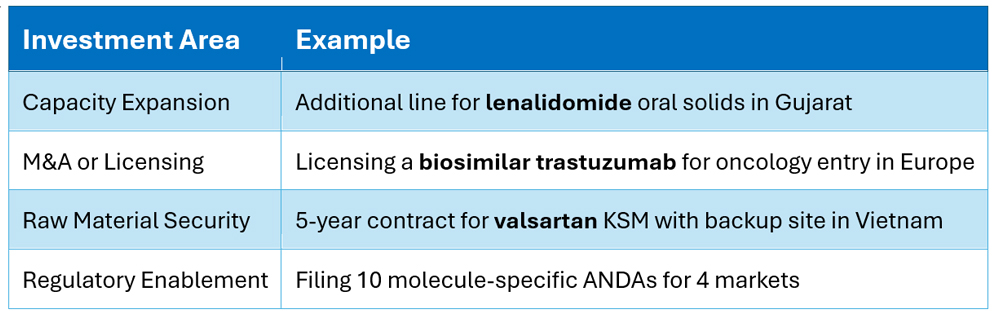

💰 What the Plan Drives: Molecule-Level Investment Decisions

A successful LRP informs where and how to invest — molecule by molecule:

🤔 Final Thoughts

Pharma long-range planning is no longer about broad volume trends or category-level views. It’s about molecule-level decisions — rooted in science, shaped by regulation, and scaled through strategic operations.

Let’s evolve LRP from a spreadsheet exercise to a strategic weapon.